ear River Review

AnAnthologyofPoetryandProse

byBearRiverWriters2008‐2009

B

Bear River Review

BearRiverWriters2008‐2009

KeithTaylor

RichardTillinghast

MaryKathleenAngel

arwulfarwulf

NormaBishop

MiraBowman

LeeWarnerBrooks

ElaineBurr

JacquelineCarney

RichardH.Coupe

KayeCurren

JimDaniels

JerryDennis

SusanL.Denny

MartiDodge

EricEderer

JeremyEfroymson

KellyFordon

JoyGaines‐Friedler

ChristopherGiroux

LeighC.Grant

PennyHackett‐Evans

DonHewlett

EstherL.Hur

witz

Jeff

Kass

DorianneLaux

MardiLink

ChrisLord

DianeMarty

JohnMauk

KathleenV.McKevitt

VickiMcMillan

BrendaMeisels

JenniferMetsker

PegPadnos

SueMariePapajesk

KerryRutherford

BarbaraSaunier

MelissaSeitz

SusannahSheffer

KenShelton

RobertE.Smith

HollyWrenSpaulding

JenniferSperryStei north

EllenStone

PiaTaavila

LaurenceW.Thomas

BillTrevarthen

AngelaWil

liams

AnthonyZick

InMemoriam

JaimeCourtney

JudyReid

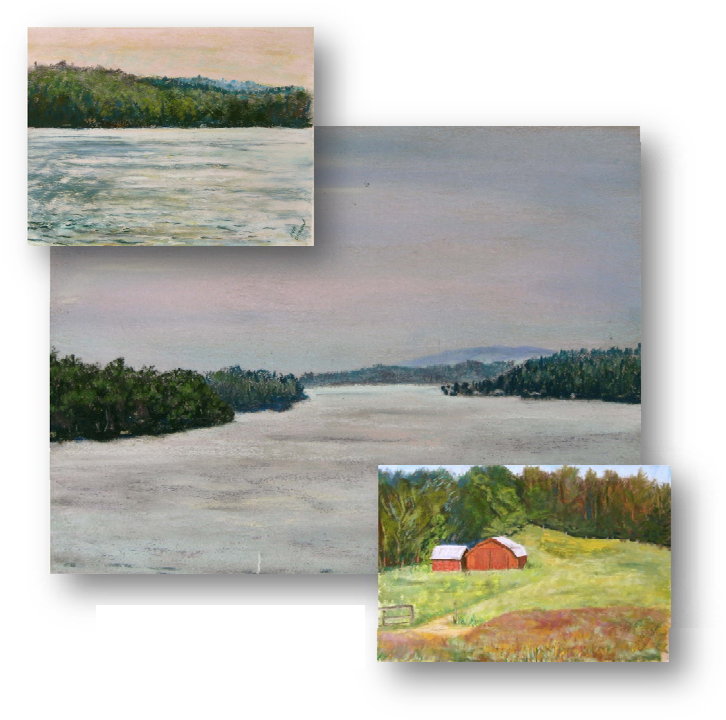

Paintingsby

AvaGilzow

H.AnneThurston

Coverartby

DonHewlett

Bear River Review

ISBN: 978-0-9795404-2-4

jÉÜwËÇ jÉÅtÇ cÜxáá

AnnArbor,Michigan48103

ear River Review

An Anthology of Poetry and Prose

by Bear River Writers 2008-2009

B

ear River Review

An Anthology of Poetry and Prose

by Bear River Writers 2008-2009

Editor

Chris Lord

Managing Editor

Kaye Curren

Associate Editor

Jennifer Metsker

Art Editor

Don Hewlett

Editorial Board

Lee Warner Brooks

Catherine Calabro

Cindy Glovinsky

Esther Hurwitz

David Penhale

Greg Schutz

Richard Solomon

Published with the support of an anonymous donor.

B

Published May 2010

by Bear River Writers’ Conference and Word’n Woman Press

© 2010 by Bear River Writers’ Conference and Word’n Woman Press

All rights reserved by Bear River Writers’ Conference,

Word’n Woman Press,

and the authors, who retain all copyright to their own material.

Cover art by Don Hewlett

Paintings by Ava Gilzow

and

H. Anne Thurston

For information on the Conference and to read

on-line issues of the Bear River Review, please go to

http://www.lsa.umich.edu/bearriver/

Printed by Kolossos Printing, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

jÉÜwËÇ jÉÅtÇ cÜxáá

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48103

ISBN: 978-0-9795404-2-4

v

Introduction

he reason the Bear River Writers’ Conference exists is to

encourage new writing. It only makes sense that we do what

we can to help some of that work find an audience. Luckily, we've

been given some financial support to implement that idea, and

also the important support of donated time. These incredible gifts

have allowed us to create a space for people to share their writing

with their Conference colleagues and with any other reader who

may stumble across it. We hope people enjoy the work and find it

helpful with their own projects.

~Keith Taylor, Director

T

Paintings on this page

b

y

Ava Gilzow

vi

s one of Bear River’s founding fathers, I am proud to assert,

a full decade on, that we have stayed true to our original

intention. To paraphrase William Faulkner, we have not only

endured, we have prevailed. Through a healthy connection with

the University of Michigan, supported by good and generous

people in our state, we have brought to our participants the best

writers and teachers in the world. At the same time we have never

stopped being an “up north” outfit. We have seen the green heron

in flight, have spotted the indigo bunting on the finial of a jack

pine, and have sat around a campfire by the lake listening to the

wild pack-music of coyotes in full cry.

~Richard Tillinghast, Founder

e thank our anonymous donor for supporting the

publication of this issue of the Bear River Review. And as

we celebrate our ten-year anniversary, we thank the founders of

the Bear River Writers’ Conference, James McCullough and

Richard Tillinghast, for charting and captaining us on this literary

voyage, and we thank Keith Taylor for his excellent direction as he

continues to keep our poetic pontoon on course. The writers in

this issue began their work at the Conference, workshopped it

there, were inspired there. Welcome to the words that flowed

from the clarity of Walloon Lake onto these pages.

~Chris Lord, Editor

A

W

vii

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. v

~Keith Taylor, Director ...................................................................... v

~Richard Tillinghast, Founder ........................................................... vi

~Chris Lord, Editor ........................................................................... vi

KEITH TAYLOR ................................................................................... 1

Canines ............................................................................................... 1

A State-threatened Species .................................................................. 1

If You Want to Find a Hummingbird Nest........................................... 2

Our Matinicus Island Seal Bone ......................................................... 2

RICHARD TILLINGHAST .................................................................. 3

Two Blues ............................................................................................ 3

MARY KATHLEEN ANGEL ............................................................... 6

A Map of the Universe ........................................................................ 6

arwulf arwulf ........................................................................................ 14

bach .............................................................................................. 14

um mitternacht .................................................................................. 16

NORMA BISHOP ................................................................................ 17

Sifting .............................................................................................. 17

Seed Stitch ......................................................................................... 18

MIRA BOWMAN ................................................................................ 19

The only way to have an organic death these days

is to be eaten by wolves ..................................................................... 19

LEE WARNER BROOKS ................................................................... 21

Matrimony ......................................................................................... 21

Flash Fiction ..................................................................................... 22

This Was Us ...................................................................................... 22

ELAINE BURR .................................................................................... 23

Aunt Lucky ........................................................................................ 23

JACQUELINE CARNEY .................................................................... 33

Close Your Eyes ................................................................................ 33

viii

RICHARD H. COUPE, Ph.D. ............................................................. 42

Elvis and a Wedding in Mississippi .................................................. 42

KAYE CURREN .................................................................................. 46

Zilka and Me ..................................................................................... 46

That Blank Page ................................................................................ 46

JIM DANIELS ...................................................................................... 47

Packing My Own ............................................................................... 47

Pyramids, Mexico ............................................................................. 48

Delivery Room .................................................................................. 50

JERRY DENNIS .................................................................................. 51

An April Shower ................................................................................ 51

SUSAN L. DENNY ............................................................................... 54

Graduation Day ................................................................................ 54

An Audience of One .......................................................................... 55

MARTI DODGE .................................................................................. 56

House Cat Rules ................................................................................ 56

ERIC EDERER .................................................................................... 61

Coffee and Cauliflower Soup ............................................................ 61

JEREMY EFROYMSON .................................................................... 63

Excerpts from “Shall We Accept this Pizza?” .................................. 63

KELLY FORDON ................................................................................ 71

Go-Go Boots ..................................................................................... 71

JOY GAINES-FRIEDLER .................................................................. 73

A Pheasant is Crossing I-75 North of Grayling ................................ 73

Assisted Living .................................................................................. 74

CHRISTOPHER GIROUX ................................................................. 75

Garden .............................................................................................. 75

Uprooted ........................................................................................... 76

LEIGH C. GRANT .............................................................................. 77

A Cradle for Small Things ................................................................ 77

ix

PENNY HACKETT-EVANS .............................................................. 81

Computer Love .................................................................................. 81

DON HEWLETT .................................................................................. 82

North of Dublin, Michigan, 2001 ...................................................... 82

ESTHER L. HURWITZ ...................................................................... 84

Olive Branch Gold ............................................................................ 84

Donna Rocks (for Donna White) ....................................................... 85

JEFF KASS ........................................................................................... 86

I Don’t Know Much About You ......................................................... 86

The Long-jumper ............................................................................... 89

DORIANNE LAUX .............................................................................. 93

Elegy .............................................................................................. 93

MARDI LINK ....................................................................................... 95

Chicken Trilogy ................................................................................. 95

CHRIS LORD ..................................................................................... 104

The River Is Yours ........................................................................... 104

DIANE MARTY ................................................................................. 106

Doomsday ....................................................................................... 106

JOHN MAUK ..................................................................................... 108

No Offense (Chapter 31 from 2004) ................................................ 108

KATHLEEN V. MCKEVITT ........................................................... 112

The Ice House ................................................................................. 112

VICKI MCMILLAN .......................................................................... 120

Thunder Mug ................................................................................... 120

BRENDA MEISELS .......................................................................... 123

Push, Pull, or Get Out of the Way ................................................... 123

JENNIFER METSKER ..................................................................... 130

Excerpts from “Backyardsy”

Rainwater & Gin ........................................................................ 130

Bird Bath Lyric ........................................................................... 131

x

PEG PADNOS .................................................................................... 132

Shipwreck ........................................................................................ 132

Zig-Zag............................................................................................ 133

Trekking LGA .................................................................................. 135

SUE MARIE PAPAJESK .................................................................. 137

Two Hearts ...................................................................................... 137

KERRY RUTHERFORD .................................................................. 142

Toe the Line .................................................................................... 142

BARBARA SAUNIER ....................................................................... 145

Displaced ........................................................................................ 145

MELISSA SEITZ ............................................................................... 146

Apple Orchard ................................................................................ 146

SUSANNAH SHEFFER ..................................................................... 151

Deciding .......................................................................................... 151

A Knowledge Like Glass ................................................................. 152

How He Chose It ............................................................................. 152

KEN SHELTON ................................................................................. 153

Baptism at Bear River ..................................................................... 153

Heroin in the Heartland .................................................................. 154

ROBERT E. SMITH .......................................................................... 156

The Sacred Mounds ......................................................................... 156

HOLLY WREN SPAULDING .......................................................... 163

Not Having the Affair ...................................................................... 163

Maybe the Hemlock ......................................................................... 164

JENNIFER SPERRY STEINORTH ................................................ 165

Late Day, Traverse Bay—Sun, Acutely ........................................... 165

My Girl, Lay Down Your Burden .................................................... 166

ELLEN STONE .................................................................................. 167

Maple Leaf Life ............................................................................... 167

PIA TAAVILA .................................................................................... 169

Memorial Day ................................................................................. 169

Service Call ..................................................................................... 170

xi

LAURENCE W. THOMAS ............................................................... 171

Ghazal for a Dull Day ..................................................................... 171

BILL TREVARTHEN ....................................................................... 172

The Effort of Flying ......................................................................... 172

ANGELA WILLIAMS....................................................................... 174

What Can Save Us .......................................................................... 174

For Hard Cider in January ............................................................. 175

Saturday at 4:00 p.m. ...................................................................... 175

ANTHONY ZICK .............................................................................. 176

On the Way Back from Bear River .................................................. 176

In Memoriam ...................................................................................... 179

JAIME COURTNEY ..................................................................... 181

The Fiddler of Kumsong ................................................................. 181

JUDY REID .................................................................................... 185

Cause and Effect ............................................................................. 185

Painters ................................................................................................ 187

H. ANNE THURSTON .................................................................. 187

AVA GILZOW ............................................................................... 187

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................. 188

xii

1

Keith Taylor

Keith Taylor’s most recent book, If the World Becomes So Bright, was published

by Wayne State University Press in 2009. He has published ten earlier books,

collections of poems and stories, chapbooks, edited and translated volumes. Over

the years his work has appeared in a couple of hundred places, ranging from

Story to the Los Angeles Times, from Bird Watcher's Digest to the Chicago Tribune

to Michigan Quarterly Review, Poetry Ireland, and The Southern Review. He has

won awards for his work here and in Europe. He works as the coordinator of

undergraduate creative writing at the University of Michigan.

_____________________________________________________________________

Canines

The coyote on Temperance Island

off Waugoshaunce (which might mean “Small Fox”)

seems young. Perhaps he’s desperately

hungry, leaping above tall grasses

after red-winged blackbirds and robins

or tearing across sand under gulls,

but he looks playful, a dog bounding

on the beach, filled with innocent joy.

A State-threatened Species

for Sara Alderstein-Gonzalez

The wavy-rayed lampmussel, yellow

or almost green, needs the small-mouthed bass

to host its young. Females siphon sperm

floating randomly in the river

then lure the fish with a fake minnow,

squirting fertilized eggs into gills.

In a month the juveniles fall off

into sand. They try to start again.

2

If You Want to Find a Hummingbird Nest

for Dave Ewert

lie down on a long abandoned road

in a northern forest—a warm day

with just a few insects—and look up.

With luck you might see a hummingbird

stopping between dead twigs of red pine

collecting shimmering gossamer

from spiders. With more luck you might see

her carry it off to line her nest.

Our Matinicus Island Seal Bone

for the Owens

I’d love to say we discovered it

while walking the south beach, opposite

Crihaven, out in the Atlantic

spray and wind, buried between cobbles.

But we found it bleached on your back porch,

this white, wing-like shoulder blade of seal.

You let us take it for our window

ledge, safe now, shaded by our humid oaks.

3

Richard Tillinghast

Richard Tillinghast co-founded Bear River and was director through 2005. Richard

writes and publishes poetry, essays, travel writing, and translation. He is the

author of ten books of poems and three books of essays. In 2008 a collection of

poems, The New Life, came out from Copper Beech, along with a collection of

essays, Finding Ireland, from the University of Notre Dame Press. In 2009 he

published Sewanee Poems and Selected Poems, which collected his work from a

forty-year career and, with Julia Clare Tillinghast, he published a book of

translations from the Turkish poet Edip Cansever called Dirty August.

_____________________________________________________________________

Two Blues

Two blues—one called serenity,

one looks like the gathering storm.

I had a tube of each in my paint box in art school.

Colors spoke.

Two blues,

the bland and the profound.

The ho-hum of a sky over Southern California—

you could call it bleu celeste or Egyptian blue.

Canaletto ground it out of lapis lazuli

for his Venetian skies.

That other blue might

paint the scary ocean depths

off the Cape of Storms,

the color of the sea in Winslow Homer’s “Gulf Stream,”

terror in the black castaway’s eyes

almost blanked out with titanium white—

perhaps the same pigment

Homer daubed on as turbulence

atop the cobalt blue waves

running battleship grey through the comfortless Gulf Stream.

Sharks circle, knowing they will eat red meat

when night falls.

4

Those two colors tutor us in disaster,

at first as we have no hint of anything gone amiss,

anything to threaten our obliviousness,

our sense that life sparkles,

that there is such a thing as a career,

goals to be set and achieved.

Sometimes existence becomes a substance so depleted

one says to oneself:

If I can just make it across while the green walking light

stays illuminated,

then I’ll walk halfway down the block

one step at a time,

watch the footing,

then back to the apartment,

make tea and, grasping the tray firmly with both hands,

inch back upstairs.

Though surely existence is limitless—

the spirit’s measureless reach,

all the mind does,

memory’s scope and inside-outness.

All that one understands now

which one previously had not.

To look out at traffic,

hear a taxi honk its horn,

and not have to venture out into otherness.

Recovering from an accident where one is obliged to

get both feet onto a step before moving

down to the next,

how enlivening it is on such a morning

to sit by the radiator and read sentences like these:

Drake had him beheaded alongside the gibbet from which

Magellan hung his mutineers, Quesada and Mendoza,

fifty-eight winters before. Wood preserves well in Patagonia.

The coopers of the Pelican sawed the post and made tankards

as souvenirs for the crew.

5

Two blues open the world.

I’m almost glad I fell.

How else would I be made aware

of those realities the staff in the emergency room

see nightly

and gladly try to hide

behind their talk of Valentine’s Day?

And these bruises on my face—

purple of the two black eyes

rainbowing to the mood indigo Duke Ellington wrote about.

Next an unsavory yellow

like the rind of a gone-off Persian melon

scattered among coffee grounds and empty raki bottles

outside a waterside restaurant in Istanbul

on the last day of August.

Burgundy blooms under my eyes

like the velvet of a sultan’s caftan,

and then they glow with that

red in the morning

where sailors take warning.

6

Mary Kathleen Angel

Mary Kathleen Angel recently completed a bachelor’s degree in English at

Oakland University. She is new to fiction writing, and is grateful to the OU donor

whose scholarship award allowed her to attend the 2009 Bear River Writers’

Conference. The lessons she learned in Eileen Pollack's fiction workshop at

Bear River will remain invaluable guides. Her short story, “A Map of the Universe,”

had its origin in a character-driven writing exercise from that workshop.

_____________________________________________________________________

A Map of the Universe

alt crouched down on the floor in the spare room and lifted

the dust ruffle on the bed. He pulled out a clear plastic box

of Christmas wrapping paper and a long, cardboard box with

some of Phyllis’s sweaters in it. Then he extracted a small,

powder-blue suitcase and popped the silver lock. When he lifted

the lid, he saw that it was full of long-forgotten, black-and-white

photos. On top was a picture of Phyllis standing in front of the

house with their son, Michael, in her arms. The date on the back

was 1954, the year they’d moved into this house. Walt shut the

suitcase and struggled to his feet. It was an interesting find.

Most Sundays, Walt’s daughter, Barbara, visited with her

husband and kids. Last Sunday, she had made dinner at his house.

While it was cooking, she went into the hall closet to look for a

tablecloth and discovered Phyllis’s coats still hanging there.

“Why do you still have these, Dad?”

“I don’t know. They’ve just always been there.”

“Maybe you should start going through the house,” Barbara

suggested. “I’ll bet there are a lot of things you could get rid of.”

“What, you think I’m gonna die soon? Are you planning to put

me in a nursing home?”

“No, Dad. But why wait until the last minute? Look what

happened to Mom.”

Neither he nor Phyllis had expected the heart attack that left

her dead in front of the stove that night nearly two years ago. Not

that either of them were at an age where death was unexpected.

It’s just that you never really think it’s going to happen that day.

W

7

Barbara was right. He should be the one to clean up his own

mess. So he had begun looking into closets and cupboards and

places he had never bothered with before. Phyllis had always been

the one to locate things, and now he realized that much of his own

home was a mystery to him. That was how he discovered the

secret of under-bed storage.

Walt carried the newfound suitcase downstairs to his den and

set it next to his comfortable chair. He groaned as he sat down,

sighing once he was fully lowered. A weak, winter sun slanted in

through the window.

The den was Walt’s haven. When he was a commercial

illustrator, he had spent nights and weekends working in this

room overlooking the backyard. Now long retired, Walt painted

for his own pleasure. His latest creation took up most of the wall

opposite his chair. Its subject was big—the entire universe, as he

conceived it—a collage of knowledge, inspiration and imagina-

tion. He had painted all of the major galaxies and some important

stars and black holes. When he worked on this project, nearly

every day adding little points of interest or embellishments, he felt

as if he were putting together the pieces of a puzzle. Of course,

things were distorted. His own solar system was much larger than

any of the others, and if a particular quasar or red giant interested

him and he wanted to paint it intricately, he would illustrate it on

some art board, cut it out and fasten it by a stiff wire that

protruded from the canvas. The evolving three-dimensional

painting fascinated his grandchildren who, whenever they came

to visit, would run in to see if anything new had appeared.

At the very edge of the canvas was the most distant object in

known space, A1689-zD1, a galaxy about 13 billion light years

from earth. Tacked onto the painting, just outside the edge of that

furthest boundary, was a picture of Phyllis that Walt had taken

when they were in Florida the winter before she died. Her smile

was as broad as the comfortable body she had built around herself

over the years, and she looked like a sun shining over creation.

Settled into his chair, Walt popped open the suitcase and put a

pile of photos in his lap, just beyond the perimeter of his abundant

belly. He shuffled through the photos: Phyllis riding a bike in

Bermuda, on their honeymoon; a picture of himself on the island

of Guam during the war in the South Pacific, the palm trees

behind him swaying in the hot wind; his brother, Pete, who had

8

died in the war; his whole family when he was about eight years

old, standing on the porch of the house on Belmont. He was the

youngest-born and the only one left. He stood up and pasted the

family photo along the border of his painting. As the afternoon

went on and Walt continued going through the suitcase, he added

more photos of the deceased until the painting was wreathed by

people.

Near the bottom of the suitcase, Walt came across a picture of a

young woman kneeling in the sand. It was a photo that he had

taken of Edna Beauchamp at Jefferson Beach, back when it was

still an amusement park. It must have been about 1946. The old

wooden roller coaster loomed in the background. Walt could

almost hear the far-off screams of the people on the ride as they

hung at the top of the big hill for an eternal second, the tracks

below dropping out of view as they rounded the top and then fell,

slowly at first, until the pull of gravity made them race toward the

earth.

Walt had nearly forgotten about the photo. He hadn’t seen

Edna since not long after that and for that reason, she looked the

same in his mind as she did in that picture—slightly sunburned,

fresh and healthily young. She was smiling the Marilyn Monroe

smile that all the blondes were copying back then—head slightly

back, eyes half-shut, lips parted just a little. Pieces of her wavy

blonde hair were upset in the nicest way by the wind.

Walt left the photo on his lap for a long time, remembering a

few things about the day—the bus ride and the walk down the

dusty road to the beach, the picnic basket full of lunch, dancing at

the pavilion after dark. It was as if Edna had stepped out of the

fog, just inside that area where things were visible again. She had

surprised him that way once before, when she had sent him a

consolation card after Phyllis’s death. At that point, she’d been out

of his life for nearly 60 years. He wasn’t sure how she’d heard

about Phyllis’s passing or how she’d found him. His guess was

that she was a diligent obituary reader. He had read the card and

put it in the drawer of his desk, keeping the envelope with her

return address. About a year ago, he had dialed information and

penciled her phone number onto the envelope, but for some

reason, he had never called her.

There were a few other photos of Edna in the suitcase—in front

of the lighthouse on the island, leaning against his sage green

9

Pontiac Torpedo, wearing a New Year’s hat and blowing a horn.

Phyllis must have gone through these photos at one time or

another. She must not have minded them, and she shouldn’t have,

of course. They were just pieces of his past.

Walt went to his desk drawer and pulled out Edna’s card. He

did this quietly, as if trying to avoid observation, and then he

went back to his chair to read it again. In it, Edna gave a short

synopsis of her entire life. She had moved back to Windsor in

1951, married, had one child, a son. She listed the events without

revealing the emotions that accompanied them. “My husband

killed himself when Jack was nine years old.” She had never

remarried. At the end, she apologized for running off in 1948.

“A twenty year old girl can’t know what it is she wants in life,”

she explained. There were a lot of details missing.

When Walt’s stomach began to rumble, he took the photo of

Edna to the kitchen with him. On the little table by the window

was the vase of flowers that he refilled each week in honor of

Phyllis. While he ate his dinner, he leaned the photo of Edna

against the vase and looked cautiously over at the space that

Phyllis had always occupied at meals. “There isn’t anything

wrong with wanting to know how she is. It’s hard to be alone,

you know.”

After Walt rinsed his plate, he went back to the den. As Phyllis

watched from her perch at the top edge of the painting, he dialed

the number on the envelope. A generic answering machine

message told him that he had the correct number. His voice shook

a little. “Yes, this is Walt Wieczorek, calling for Edna Beauchamp.

If you’re there, I’m just wondering … just wondering how you’re

doing.” He left his number and hung up, thinking he should have

said more. That was his problem, he thought, suddenly. He

always said less than he felt.

After all these years without a sound from Edna, Walt was

impatient for the phone to ring. He read the paper, watched the

news and went through the mail. There were a million reasons

why she might not call back right away. Perhaps she was out or

staying with her son. She could be sleeping or sick in the hospital

or…

At 7:30, Walt put on his boots and coat, slipped the photo into

his pocket and trudged through the slushy snow to the bar on the

corner where he met Herb Goetzke on Fridays for a beer. The bar

10

was one of those dark places that have little use for windows or

atmosphere, built into the neighborhood over half a century ago

as a place for auto workers to drop in on the way home from work

and spend some of their paycheck.

Herb was sitting at the bar, hunched over, his eyes on the

television behind it. Walt sat down next to him and ordered a

beer. Then he pulled out the photo of Edna and set it on the bar in

front of Herb.

“Marilyn Monroe?” Herb asked, pulling out his reading

glasses.

“No, a girlfriend from long ago.”

“You know she doesn’t look like that anymore, don’t ya?”

He told Herb the story—how he’d met Edna at the dance

pavilion on Boblo Island just after he’d come back from the war;

how he’d been crazy about her, but for some reason he had never

gotten around to asking her to marry him. It was too long ago to

remember why. He had been busy in art school and working as an

usher at the United Artists movie theatre. Then she had left,

suddenly.

“Did she run off with a guy?”

“I don’t know. I only know she went to California. She called

me when she got out there, crying I remember, saying she was

sorry. We never spoke again.”

“California, huh? Maybe she had dreams of becoming an

actress.”

Walt agreed that was possible, but it didn’t really matter. “If

my heart was broken, I hardly remember that now. I suppose I

just got busy doing other things.”

After Walt finished his beer, he went home. Without removing

his coat, he went to the phone to see if there was a message

waiting. Strangely impatient, he dialed the number again. The

same generic voice greeted him.

He was restless. He didn’t know what had come over him.

After all the time that had passed, he suddenly wanted to waste

no more of it. He went back out onto the front porch, not sure

what to do with himself. He thought he must look foolish to

anyone watching, but there was nobody around. The neighbor-

hood was quiet except for a dog barking somewhere behind one of

the houses across the street. He walked out to his car and stood

11

next to it. Then he got in and just sat inside it for awhile. Not sure

what he was doing, he started it up.

Twenty minutes later, he was on the bridge that linked Detroit

to Windsor. Far below, stray sheets of ice floated lazily on the

surface of the slick, black water streaked with bright lights from

the city. When the bridge began its descent, he saw a sea of snow-

covered rooftops beneath him. One of them belonged to Edna.

At customs, the officer asked the purpose of his visit. He

stammered, feeling as if he were hiding something. “Going to visit

an old friend,” he said. The officer was kind enough to give him

directions to Rosedale Avenue.

Edna’s neighborhood lay in the shadow of the bridge, beneath

its dark undersides and the ever-present sound of cars passing

overhead. Her house was a brown-brick bungalow with a large

porch and a small yard. Walt parked in the street and looked at

the dark windows of her house. Was she really still living there? If

so, was there anything left of that girl with the spark of life in her?

He thought about knocking on the door, but it didn’t feel right.

She might be sleeping.

He decided to write a note, but he searched his car for paper

and found nothing. The only thing he had to write on was the

photo from 1946. He hoped that seeing the picture again would

bring good memories rather than a sense of loss. He turned it over

and wrote, “For everything there is a season.” Then he put his

name and phone number on it. He felt poetic, romantic, not quite

himself, and he sat there for a long time before he gathered the

nerve to approach her house. His steps rang out on the old wood

floor of the porch, and the mailbox creaked as he lifted the lid to

drop in the photo. He lingered there a moment, feeling the

warmth of proximity. After that, he drove north along the river

toward the heart of the city, thinking about everything that had

changed since he was a young man.

Walt kept busy the next day, but he was careful to stay near the

phone. In the late afternoon, after the house had been silent all

day, he called the number again, and a man answered. Walt told

him he was looking for Edna Beauchamp. The man said he didn’t

know an Edna Beauchamp. The man almost hung up, but Walt

said, “Wait!” and asked if he had called the address on Rosedale

Avenue. No, he had called a house on Wyandotte. He had been

given that number when he moved to Windsor last year.

12

Just before dinnertime, the phone rang. The young woman on

the other end asked Walt if he had left the photo in her mailbox.

She said the woman was very beautiful. She did not know an

Edna Beauchamp, but she suspected they had bought their house

from her son, Jack Beauchamp.

Walt asked if she knew what had happened to Edna

Beauchamp—was she still alive? The woman didn’t know. He

asked if she had Jack Beauchamp’s phone number, and she

hesitated. “Yes, I do. I suppose it’s all right if I give it to you. I can

see you’re just an old friend.”

As soon as she hung up, Walt dialed the number. A woman

answered the phone and he asked for Jack. A moment later,

Edna’s son was on the phone. Walt got right to the point, telling

him he had known Edna years ago and wanted to get in touch

with her.

“I’m so sorry, Walt. My mother passed away almost a year

ago.”

Walt sat down. It wasn’t that he hadn’t thought it was possible,

but he had hoped there was still a little time.

“Was it a peaceful death?” he asked.

Jack said it was. She had been sick but comfortable, and it

seemed as if she had just fallen asleep.

After Walt hung up, he sat in his chair in the corner of the den,

watching day turn to evening. As the sky became a pink backdrop

to the bare, dark branches of trees, the snow turned a soft blue.

Walt could see the dried remains of his garden peeking up

through the snow. As the room dimmed, the angles of the furni-

ture softened and Walt melted into the shadows. He could barely

see his painting now. Its flat patterns and protruding shapes were

indistinguishable; its dark areas, absorbing what little light

remained, became that unfathomable space they represented.

Walt reached up to turn on the lamp. The yellow light shone

on the dome of his head, shadowing its furrows and liver spots

that might look like the ridges and craters of a barren planet to

some small insect circling him. The canvas leaning against the

opposite wall came back to life, the crowd of people along its

edges looking at Walt.

The photo of Edna in front of the lighthouse lay on top of the

suitcase. She was squinting in the sunlight, smiling an eternally

youthful smile. It was spring when he took that photo, still a nip

13

in the air. He remembered riding home on the old riverboat that

night, leaning against the railing and watching the homes of

Amherstburg pass by while people danced to big band music on

the wooden floor in the center of the boat.

Walt rose slowly from his chair and brought the photo of Edna

to his desk. He smeared some glue onto the back of the photo and

then walked over to the painting, looking for an open space along

its edge. He pasted Edna just beyond the Boötes Supercluster. He

hoped Phyllis wouldn’t mind. After all, she still had the highest

position on the painting.

Then, he stood back to look at the state of his universe. There

was hardly an empty space in it.

14

arwulf arwulf

arwulf arwulf was involved in performance poetics at the original Performance

Network and at public readings in Ann Arbor, Chicago and Detroit. Poetics are an

essential element in his radio programs on WCBN, WEMU and WFMU. arwulf

attended the Bear River Writers’ Conference in 2007, 2008, and 2009,

participating in workshops led by Bob Hicok, Keith Taylor, and Richard Tillinghast.

The effects of each of these workshops are in evidence whenever he writes

shopping lists, poems, essays or musicological schemata. The Conferences taught

him to consult with the natural history of Michigan to discover deeper meaning

and relevance in this life.

_____________________________________________________________________

bach

not far at all from the trailhead

near where you been sleeping every night

a brook is undulating through the forest

what has stopped me here for awhile

as i near the end of this particular

peregrination, is the perfectly

balanced polyphony of the

bach chorale made by the same water

as it tumbles over roots, rocks

and fallen branches

upstream of here

the basso continuo

while the gentlest altos

15

and sopranos imaginable

sing from each bend of this

baby rattlesnake brook

the place where it ultimately

passes under the forest path

to continue through fern

loam and swamp grass

generates a complementary

bass line so that the full length

of the segment of the brook

that is visible & audible to me

from where i stand

becomes one ensemble

or, given the fact that the same water

plays the entire brook, one instrument

the brook, as a chorale, is scored for

soprano, alto, tenor, bass and continuo

may it continue

16

um mitternacht

from eduard mörike & hugo wolf

through sviatoslav richter & dietrich fischer-dieskau

Alkman, who lived in Sparta during the seventh century Before

the Common Era, wrote hymns, preludes and songs to be sung by

choirs of young women. One fragment describes a world where

everything is asleep. Mountains and ravines, worms, moles and

centipedes; mammals that live in the hills and entire societies of

bees; behemoths, krakens, leviathans, deep sea creatures that

never see the light of day; birds of every size and feather, all are

fast asleep.

In nineteen hundred and twenty nine Federico Garcia Lorca came

to New York City, just in time, as he put it in so many words, to

see a great sheaf of dead money go sliding off into the ocean. The

big city seemed altogether too big for this Andalusian, who said

that back home everything was tiny by comparison. Here the

buildings were impossibly tall, and people were jumping out of

them because of the money.

At four o’clock in the morning, Federico stood in the middle of the

Brooklyn Bridge staring out at the countless lights burning just

everywhere as far as the eye could see, and there and then he

wrote: everyone everywhere is wide awake. Nobody anywhere is

asleep. The iguanas will come to bite the unsleeping men who do

not dream. Everything is awake, said Federico Garcia Lorca to the

Brooklyn Bridge at four A.M. in the jet black dawn of the age of

insomnia.

17

Norma Bishop

Norma Bishop, a native of the Great Lakes region, spent 20 years in California,

where she was a feature editor for the magazine Coastal Woman and a feature

contributor to the Santa Barbara News-Press. She returned to the Great Lakes in

2005, where she is a museum director, writing poetry and working on a novel set

in Wisconsin. Bear River in 2009 was Norma’s first writing conference. Sharing

tribulations, inspiration, and insight in a community of writers and being

nourished by the serene setting gave her a charge of energy. Norma thanks Laura

Kasischke and those who attended her workshop.

_____________________________________________________________________

Sifting

Tracing your name

on steam-scrimmed, silvered glass,

I watch each letter weep.

And I become ribs

caught in sand and sifting time

from a sea opaque with silent grief,

lungs filling with brackish breath

of rivers,

of mudflats of oysters

sucking silted time.

Corridors pearled

in nacreous light reflect

your shadow bent by tides.

Glistening crescents,

scales refract a thousand moons:

a mosaic of light in drifts of silt.

Time, falling as sun on sand,

fills harbors

near headlands, there sheltered

from rock and frothing seas—

where you wait for me.

18

Seed Stitch

She holds the yarn in fingers

slim and white as birches lining the shore.

The yarn, a twist of colored strands, forest duff—

green spruce,

brown, scaled cones,

russet lichens,

gray, water-worn granite,

bitter-yellow beech leaves,

and silvered blue of the lake’s wind-swept mosaic.

She knits the colors into a forest fabric,

soft purled hills like ever-traveling swales that ripple inland from

lakeshore,

knit stitch vees, crotches of forked aspen and elderberry where

orioles nest.

She shapes sinuous sleeves

and a windbreak collar deep as the cedar copse.

A dandelion seed, piloting the wind,

lights on her wrist.

Deftly she grasps it between moon-white nails of forefinger and

thumb

and plants it in the next stitch, one furrow from the finishing.

She’ll wait for the first rain and,

in the meadow, slip it over branch-boned arms.

19

Mira Bowman

Mira Bowman has recently graduated from the University of Michigan with a BA in

English and creative writing. She was privileged to participate in the 2009 Bear

River workshop with Jerry Dennis where she learned to hone her skills in using the

surrounding wilderness as a source of inspiration. This is Mira’s first published

work.

_____________________________________________________________________

The only way to have an organic death these days

is to be eaten by wolves

Imagine it. At first only the vague inkling

of danger followed by your usual skepticism:

“Relax. You’re fine. Nothing bad

is going to happen.”

But then it does happen,

as bad things tend to do.

There will probably be snarling.

You’ll probably do something futile:

pick up a stick, throw rocks, maybe

try to climb a tree.

Adrenaline will show up too,

only it’ll be different from previous experiences.

It won’t stop when you get off the roller coaster.

You won’t be able to soothe it with a corn dog.

And soon you’ll stop thinking

“Fuck, I’m being eaten by wolves!”

stop comparing it to novels about the wild

because, fuck, you’re being eaten by wolves.

Pouncing. Biting. Slurping.

And bam, you’re dead.

But think about it:

better than a nursing home or another car crash,

you get to feed some creatures, which,

face it, you’re probably part of the reason

they’re hungry now anyway.

20

Then whatever’s left will decay

and flowers will feed there,

popping up in your skull holes,

and your soul, or whatever,

doesn’t have to worry about escaping

heavy coffin lids, and maybe,

way out there away from all of that

ghastly make-up and embalming fluid,

you’ll have enough space and peace

to turn into a caterpillar,

which wouldn’t be so bad.

21

Lee Warner Brooks

Lee Warner Brooks has been at Bear River every year except for one since 2003.

He has published sonnets in journals like The Iowa Review, Light, and Passager.

In 2009, his book Novlets: 67 Sonnets was published by the Legal Studies

Forum, and later that year an excerpt from the Journal he has kept since 1977

was published as part of a book called Keeping Time: 150 Years of Journal

Writing, by Passager Books. At Bear River in 2009, Dorianne Laux challenged Lee

to write poems that were not sonnets; hence, the three free-verse poems in this

issue.

_____________________________________________________________________

Matrimony

You asked me

How did we end up married back then?

There was no license no church no ceremony

But there we were

living the same life

owning the same car

And then there was a long twilight time

It was as if

we both married other people

We did

We both married other people

You gave me jazz

Eric Dolphy on flute

playing “You Don’t Know What Love Is”

But we knew

We both knew

Didn’t we?

And I’m asking you

How did we ever end up divorced?

Where’s the decree?

Dammit—I married you first

22

Flash Fiction

I can’t resist you, she said. So I must go back to my husband.

He doesn’t exactly love me, but he needs me.

But—I need you, he said.

I know, she said, but you know how to cook.

This Was Us

Two beetles coupling

on the last flat surface

of a mostly eaten rose leaf

while the hummingbird kisses

into the orange flowers

behind the red barn—

inserting himself

and sucking in

one quick

hunger.

23

Elaine Burr

Elaine Burr received a Hopwood for a collection of short stories when she was a

student at the University of Michigan, has had stories published in many

magazines, and four novels published under her married name, Elaine Stienon.

She was in Richard McCann’s workshop at the 2009 Conference, and revised

“Aunt Lucky” after she returned home. Elaine learned to consider the actual

writing and the act of publication as two separate activities, and not to give up on

a work until it has been submitted to various places at least thirty-five times,

maybe more.

_____________________________________________________________________

Aunt Lucky

alk about weird childhoods. You try growing up in a dinky

little Midwestern town when you’re half-Chinese and half-

British, and see how you like it. What with the hassles at school,

the scuffles on the bus, and my being chased home from the bus

stop half the time, my parents must’ve wondered if they could

even raise Eurasian kids to adolescence in that place.

Most of the persecution took aim at me. My brother George

was quiet, a good student, and my little sister Beth was sweet and

pretty. Me, I was the fighter, the feisty one, scrappy, always in

trouble.

How did three Sino-British hybrids end up in southern

Michigan? Man, I really wondered. The way it happened, my

father managed to make it out of China just ahead of whatever

civil disturbance was going on at the time. It was a big deal,

according to him—a harrowing journey, but I bet it took him twice

as long to tell it as it probably did to happen. He did time at the

University of Michigan, a graduate student in philosophy, and

started on a different journey—marriage to an undergraduate

from London.

But I wanted to tell you about Michigan. We had this small

plot of land just outside Ann Arbor, a sprawling frame house in a

little farming community. We raised vegetables—beans, tomatoes,

lettuce, squash. George and I would’ve liked some chickens too,

but we were all vegetarians and had no use for chicken meat.

T

24

George, being the oldest, was sent every week to buy eggs from

the Luckners down the hill.

I remember my mother Margaret, slender, taller than my

father, moving briskly around the kitchen as she prepared the

mid-morning meal—whole grain rice and cooked vegetables

flavored with soy sauce. She would scold in her clipped accent:

“Jeffrey, now try to behave. Get your fingers out of the bean cake.

And stop tormenting the cat. Go wash your hands, right this

minute.”

She really worked up a sweat, chewing me out (not that I

didn’t deserve it). She would threaten to send me down to Aunt

Lucky: “She knows how to deal with you.” I tried to make noises

about what a drag that was, but I was secretly hoping she’d do it.

Her real name was Emma Luckner. A retired school teacher, she

lived with her brother the poultry farmer. She was not Chinese or

British, but about as American as you can get. For one thing, she

had Native American ancestry—Ojibwa, she told us once. She had

one of those full faces, dark eyes that crinkled at the corners when

she smiled, and short, grayish hair, not kinky, but full; it seemed

to frame her face like a wreath. She was stocky, not too tall—about

the same height as my father—although I remember the time

when she seemed about as tall as anyone I’d ever seen. The main

thing I recall was this look of expectancy, as if she was waiting for

something. If it was marriage, she was still waiting.

My sister is whimpering, clutching the towel to her chest with

both hands. I hold on to her shoulder as I ring the doorbell.

“Come on, Beth. Try to stop now. How can we tell her if you

keep crying like that?” Thinking please be home Aunt Lucky. Please

let it be you coming to the door and not your brother.

When she opens the door, I try to think how to tell her. Finally

I say, “Beth won’t stop crying.”

By this time Lucky is stooping down, taking the towel gently

from Beth. She turns back the corner of it, and there is the tabby

kitten in a pool of blood, its head smashed in. I avert my eyes, not

wanting to see again, feeling the sickness spreading in my

stomach like the first time.

Lucky quickly closes the towel, looks at me. “When did it

happen?”

25

“Right after school. Out in front of the house—this truck—”

Beth speaks, the first time since the accident. “Please make him

well.”

“I can’t, honey.” Again looking at me. “Did she see it happen?”

“No. Just after. But I saw it. The truck never even slowed

down.”

“Beth, listen.“ Lucky’s voice is soft like faint music. “Your

kitten is no longer here. He’s gone to another place, and he’s not

hurting anymore. This body is all that is left, and we’ll take care of

that right now. Come with me. I’ll just get the shovel.”

I marvel at the way she takes us through the burial process. I

marvel in the first place that Beth is no longer crying—I thought

nothing would make her stop.

“We’ll put him right here, under this big pine. Now, Jeffrey,

you dig us a grave.”

When it is deep enough, Lucky stoops to put the kitten in,

towel and all. We take turns filling the hole, Lucky with the

shovel, Beth and I with our hands. I feel bad, disgusted at the

weakness that makes my legs feel like giving way.

“How can someone see a little cat crossing the road and not

even slow down?”

“Well, Jeffrey, maybe they didn’t see him. It was an accident—

something that shouldn’t have happened. I’m sorry. Now...”

Lucky leaves the shovel, straightens up, invites us to take her

hands. “I’m going to say something—it’s like a prayer. We’re

going to put him into the hands of the One who takes care of all

creatures—the Great Spirit. I’ll speak in a language you don’t

know—it’s my first language.”

It is a language of woods and meadows; the tone is calming,

cleansing, like a fresh breeze blowing over us. Then her voice dies

away, becomes part of the rustling of trees, of wind in the tall

grass. We sit together at the edge of the woods, and she shows us

things—the light falling in bright pools among the tree-shadows,

shining on a strand of spider’s web, moving in patterns on the

pine tree trunks.

“When you see the light dancing on the tree trunks, you will

remember your kitten and the good times you had with him—you

will think of life and how good it is to be alive now, and how we

should treasure every good moment while it is happening.”

26

A few days later Aunt Lucky is at our door.

“Now, Jeff...listen, Beth. I’ve spoken with your parents about

this. This kitty stays indoors—she’ll never go near the road.” From

under her coat she produces a kitten the color of wheat, of straw

with sunlight on it, the face tinged with dark brown.

“It’s a special breed of cat—it’s Siamese. I have a former

student—an old friend now—and her cat had a litter. See how

little? She was the runt, the smallest one, and my friend just gave

her to me.”

So we had a cat from the Orient, thanks to Aunt Lucky. We named

it after her. And that cat stayed with us all the years we were

growing up—even moved to Seattle with us.

Just as the war started, our aunt and two cousins came over

from England as refugees. My cousin Stanley had eyes as blue as

our Lucky cat, and hair so blond it was white. He was six months

older than me, sort of in between George and me, and he was still

upset about leaving England and all his friends.

“In a convoy, Jeff. With a battleship at the front—a big one.

And one at the back.”

War makes people crazy; I begin to sense it then. My cousin,

sharing my bed with me, wakes me up every night that first week.

“The Germans are coming. Hear the planes?”

Rushing to the window. “It’s got a Nazi insignia. Look.”

“Stanley, there’re no German planes here. This is America.”

“No—look! Can’t you see it?”

“Those are just planes. Hitler can’t get this far.”

Sunday afternoon. The grown-ups are having tea in Aunt Lucky’s

front room—my mother, my aunt and my English girl-cousin,

who is older than George and wants to stay with the big people.

She is kind of stuffy anyway, so we don’t mind. I am out in back

with my sister, my cousin Stanley, and George. I am just noticing

that both Stanley and I are taller than George.

Stanley looks around. “There’s no bomb shelter.”

“We don’t need one,” George says.

“What do you do when the planes come over?”

“There’re no bombs, Stanley,” George explains.

“But in case—”

27

George looks at me, raising his eyebrows. I say, “Maybe

Stanley’s right. You never know. Maybe it wouldn’t hurt to have a

bomb shelter or two.”

George shrugs. Stanley gets Aunt Lucky’s shovel. I get the

pick-ax. He and I spend the next hour and a half digging holes in

her back yard. George does not help.

“You guys are gonna get it.”

I am curious to see what a bomb shelter looks like. We don’t

get that far. But I do get to see what my aunt and mother look like

when they discover the holes. My aunt has a proper fit.

“Stanley, how could you do such a thing?”

While he is explaining about the shelter, my mother gets after

George and me.

“You know better than that. Why did you let him dig up her

garden?”

“Just a moment,” Aunt Lucky says. “Let me speak with him.”

My female relatives are fuming, tearing into George, of all

people; his face is red behind his roundish glasses. I chew at a

hangnail, watching as Lucky takes Stanley by the hand, leads him

over to the end of the yard. She is leaning over, listening to him,

then speaking earnestly, looking into his eyes. She talks a long

time. Finally he smiles.

When they come back, Lucky says, “He’s apologized, and now

the children will fill in the holes.”

They make George do it too. He is so pissed he can’t even

speak. I wonder what Lucky said to Stanley; he will not tell us. But

he no longer talks about the Germans coming, and the sighting of

Nazi planes stops for good.

They stayed with us for a little while and then my aunt found a

place in town. We saw them on weekends and holidays. When we

went to a movie theater in Ann Arbor and heard the audience sing

“Deutschland Deutschland über Alles” during the newsreel, I

thought Stanley was going to barf popcorn all over the row in

front of us. My mother explained.

“There’s a strong German community here. A colony of

immigrants.”

But the big trouble didn’t start till America entered the war. A

kid at school called me a Jap, and I knocked out one of his front

28

teeth. My mother cried; she thought I was already on the path to

juvenile delinquency.

Aunt Lucky’s voice: “Now, Jeffrey. Do you know what a Jap

is?”

“Well, sure.”

“It’s an epithet. A nasty name. It really doesn’t mean

anything.”

“Well, I didn’t like the look on his face when he said it.”

My mother was afraid; I could sense it. When they thought I

wasn’t listening, I heard Lucky tell her, “I think he’ll be all right.”

“Yes,” she replied. “But will we?”

On the night they have the meeting, my father comes home early.

We have our meal of rice and vegetables, and my favorite—

deviled eggs with yeast extract. A little later, around eight o’clock,

Aunt Lucky walks up the hill to our house.

“Margaret,” she says as she comes in. “I just got wind of

something. There’s a bunch of the neighbors coming by. I want to

be here when they do.”

My mother glances at me. “What about the children?”

“They can go into the back bedroom. They don’t need to hear

this.”

So George takes Beth and the cat and heads down the hallway.

I refuse to move from the table.

“I’m not going anywhere.”

Before they can argue with me, someone pounds on the front

door. Then we hear the sounds outside, voices, feet crunching in

the gravel. My father gets up, and I see suddenly that he is

stooped, his head bent, like an old man. He goes to the door and

turns the knob. My mother is just behind him, and Aunt Lucky

moves so that she is standing to his left when he opens the door. I

move too—I go to the front window so I can see what is

happening.

Neighbors are standing in a half-circle, their flashlights shining

in the semi-darkness. Some are strangers, but others my father has

worked for, repaired houses, built sheds and shelves.

A man named Nathan Richards steps forward out of the

group; all I know about him is he has this snotty daughter,

Angela, and they live in this fancy house up the hill. He is of

medium height, taller than my father, and the extra fat sort of

29

hangs on his jowls and around his neck. You can tell he hasn’t

missed too many meals in his life. He goes into this throat-clearing

routine and looks around. The rest of them fall silent.

“‘Evenin’, Chang.”

“Good evening,” my father says.

Richards gives this nervous little cough, then says, “We’ve

been having sort of a little meeting, yes, a meeting down in the

church—just the local people, and we—”

“We know all about your meeting, Nate Richards,” Aunt

Lucky says from the doorway.

“Now, Emma, you stay out of this.” He harrumphs again.

“Now, what we’re trying to say—”

“Well, say what you have to say, then,” Lucky says. “Get it out

into the open.”

Mr. Richards grips his flashlight with both bands. “Well, you

see, we’re all patriotic Americans around here, and we’ve just

decided we don’t want anyone living here who isn’t one hundred

percent united with us, now that war’s been declared, and, well,

you see—”

“Just what makes you think this family isn’t patriotic?” Lucky

demands.

“Oh, hang it all, Emma, you know as well as I do they’re

Asians. And we just don’t want any Japanese around here.”

By this time Lucky is out the door, standing on the steps beside

my father. “All right. Listen, everyone. Especially you, Nate. Clean

the cow dung out of your ears so you can hear.”

There is hooting from the circle. Lucky is using her school-

teacher voice, which really projects.

“In the first place, Chang is a Chinese name. He is Chinese, in

spite of what you thought. There is a difference. But even if he

were from Japan, he would have as much right to this piece of

ground as you or anyone else.”

She explains how my father is an American citizen now and

pays taxes the same as they do. She even puts in how he was a

refugee from the revolution in his old country, and had come to

seek safety in America. She asks what kind of example they are

setting for him and his children. By this time they’re looking

uncomfortable, glancing around, stepping backward so the circle

doesn’t seem as tight.

30

Then she really tears into them. Says stuff about how the land

first belonged to the Chippewa anyway (“That’s ‘Indian’ to you,

Nate Richards,”) and how maybe the Chippewa should just kick

the whole lot of them off. How would they feel then?

Mr. Richards’ face is turning a deep pink; he is breathing fast,

as if he has just lost a game of tennis. But Aunt Lucky is relentless.

She goes into this song and dance about how each person is equal

and of worth, even if he comes from a part of the earth most of

them haven’t bothered to learn much about.

Oh, she is magnificent, my Aunt Lucky. There is fire in her

voice, and passion. Not easily impressed, I stand with my mouth

open, thinking I would not like to be in that circle of men with

them looking less tall, less sure of themselves and more ashamed

every minute. And then I see something. My father is no longer

stooped; his head is high, and he is even smiling a little, admira-

tion and amazement on his face as he looks at her. And that’s

what I meant when I said I’d seen her stand as tall as anyone you

care to mention.

“I suggest you go and leave these good people alone. But

maybe you should apologize first.”

Richards turns then; I sense he is ready to get out of there.

Probably more than ready. Another neighbor, Mr. Judson, steps

up with his hat in hand.

“It looks like we’ve made a mistake. Mr. Chang, I’d be pleased

to have you for a neighbor for as long as you care to stay. Sorry to

trouble you, ma’am.” He nodded to my mother.

One by one they come to stand before my father and mumble

their apologies, some shuffling their feet in the gravel. The circle

disperses; they leave, disappearing into the darkness. Only Aunt

Lucky is left. She turns as if nothing has happened.

“How about some tea, Margaret? I can’t take this much

excitement every night.”

Years later. George and I are walking on the beach just at sunset.

To our right stretches the Pacific Ocean, hazy, with a bluish sheen

on the water. Just up the hill to the southeast are straggly stunted

trees, then a stand of evergreens.

I am still taller than George by a head and he is as mild-

mannered as ever, a professor of math at the city university.

Ahead of us are our families. George’s wife is Chinese, from San

31

Francisco; mine is Anglo-American. The children, four girl cousins

kicking sand at each other, all look similar—black-haired Eurasian

kids. Beautiful girls. George wants to visit China someday and try

to find more family, but I have no desire to go.

“I probably wouldn’t fit in there either.”

George and I speak freely of what happened. Since he was in

the back room with Beth and the cat, he had to rely on me to tell

him.

“I almost didn’t believe you,” he said once. “Until she got

sick.”

You see, when Aunt Lucky’s brother died and she lost their

farm, my parents took her into their home. She was old then, old

suddenly, it seemed, and crippled with arthritis. They cared for

her, and she was part of our family until she died.

“You know what she said once?” I say to George. “She said

something about how good it is to be alive, and how we should

treasure things while they’re happening.”

“She was quite a gal,” George says.

“You don’t know the half of it.”

They’re all gone now, my mother and father, and Aunt Lucky.

My British cousins, now American, are scattered in various parts

of the country, and my little sister Beth became a veterinarian. I’m

the only one without a real profession. I work as a substitute

teacher, just enough to support my family and keep on with the

freelance writing. Summers I crew on a sailing vessel that takes

tourists on midnight cruises. I don’t make tons of money, but

somehow I think Aunt Lucky would have approved.

We leave the water’s edge and head up toward the trees and

the parking lot, our bare feet making hollows in the sand. As we

enter the stretch of woods, I feel the breeze at my back. I smell the

pines and the sea-scent, a faint whiff of fish and gasoline from the

harbor.

Both George and I pause for a last look at the water, the

reflected sunset still sparkling on it in tiny points of light. He calls

out to the family, “All right! Let’s go!”

The girls scurry to get into the car, the mothers fumble with the

seat belts. The children are laughing. I am suddenly seized with

affection for them, for daughters and nieces, wife, sister-in-law,

even George—although it would embarrass him no end if I were

to acknowledge it. Strange thoughts—as if the old ones are still

32

with us, my parents, Aunt Lucky, ancestors I never even knew, all

hovering unseen in the hazy air of dusk. I turn, wishing the

moment would go on and on, this brief walk through woods, and

then I marvel that I have come across half a continent to see the

light dancing on the tree trunks.

33

Jacqueline Carney

Jacqueline Carney has been an independent bookstore owner, reported for and

edited newspapers, and written for Women’s Day and other national magazines.

She wrote mostly non-fiction before attending Elizabeth Kostova's workshop at the

2008 Bear River conference. Elizabeth’s workshop revolved around writing as

influenced by art. One of the assignments was to begin a story that had a

particular painting at its core. Klimt's The Kiss was the painting Jacqueline

selected and “Close Your Eyes” is the story she wrote. Since the workshop

Jacqueline has completed a novel and sent it to several “beta” readers.

_____________________________________________________________________

Close Your Eyes

llen stood just inside the tiny bookshop. It was exactly as she

remembered—the tomes of literary fiction, poetry, philosophy

and art consuming her like goldfish that in a feeding frenzy tore

off bits of her then darted away. It was such delightful agony and

she laughed out loud. A teenager—a boy with spiked hair and

leather pants—flashed her a pained look as he passed.

“That’s one odd old lady,” was what Ellen could almost hear

him say.

She didn’t care. Already she’d exhumed herself from the place

where recent nightmares held her sleep hostage.

A wood deck, worn but welcoming, surrounded The

Bookworm’s rear entrance and overlooked a steep, sharp-stoned

gully and its creek. Ellen loved that creek—its sounds that

changed with the seasons. In the fall, the thinned waters clinked

over stones like change in a vendor’s money belt. Ellen would sit

and listen as she flipped the pages of the latest art book. She’d be

reminded that a slower season was at hand—one that offered time

to reflect on what life had offered.

A different creek flowed in the spring. It was deep and full

from the rains—its rush disconcerting but swollen with the

promise that life will again renew itself, that change is always

possible.

Along the deck’s rails, tables and chairs fashioned from pine

branches still clustered, a bit grainier and more stained by the

weather. They bustled, as they always had, with coffee-sipping

bookaholics. Reminded of her mission, Ellen straightened and

hastened to “Religion and Philosophy.”

E

34

She never intended to browse, much less stop in the aisle of

oversized art books, but one cover in particular—a plated print of

“The Kiss”—thwarted her resolve and lured Ellen back.

It was during her high school art history class that Ellen first

viewed Klimt’s masterpiece—a poster on a wall of this very shop.

Her teacher, Miss Saunders, was a young woman so full of facts,

dates, timelines and plate titles she could have taught advanced

computer science except that, back then, there were no computers.

“You can learn something here,” Miss Saunders had railed to

her students at the end of one class, “about the difference between

the artist who merely hones a skill and one who masters true art.

Klimt’s designs are pretty, yes. And so are his women. But they

are also pathetic sex objects—especially his dear Emilie.”

From behind her black-rimmed glasses the teacher’s face had

reddened and her voice had elevated as she said the muse’s name.

As Ellen took a seat with the Klimt biography in hand, she

could still hear Saunders’ distinctive cackle.

Saunders went on. “Klimt and his Secessionist pals had little

use for anything beyond chauvinist eroticism—totally ignored the

fact that industry was the golden egg of progress—that it ensured

the world a prosperous future and women their fair share.”

An angular woman with short-cropped hair—a grackle’s

iridescent black—she had cut a sharp thin silhouette against her

shelves of art books. She’d removed her glasses as if to highlight

the gravity of her message.

“It is the artist’s task,” Saunders had droned on, “to reflect

such remarkable times, not mire in sentimental opiates. Klimt’s

rampant sexual symbolism was at best a waste of paint. His

paisleys of rich colors were lovely, yes, but what universal truth

did their application impart?”

Since fifth grade, Ellen had harbored hopes of making art her

career. Sketching was how she filled her time because girly